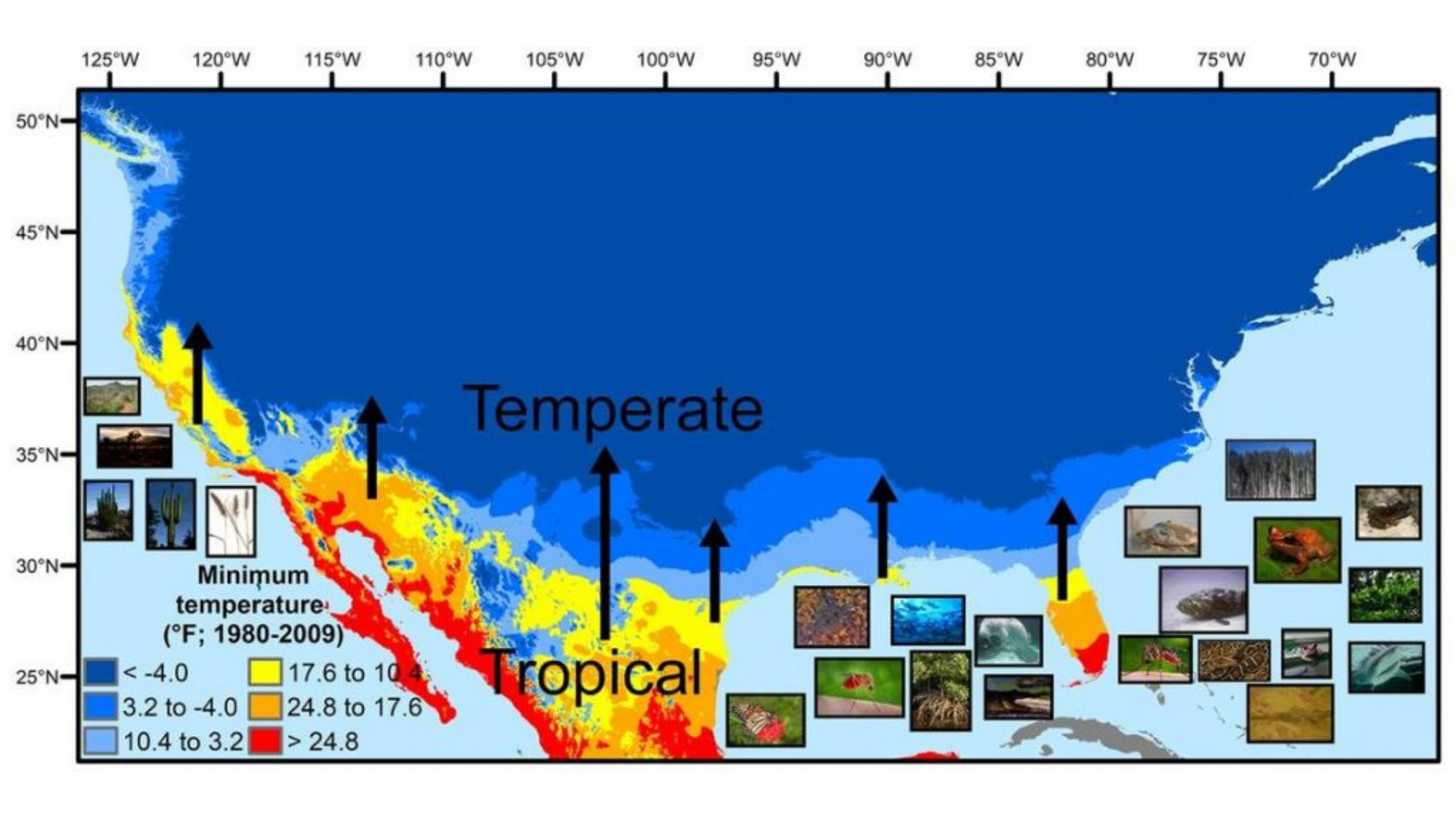

Tropical Plant Species to Move Northward as Winters Warm Due to Climate Change

Parts of US’s Southernmost States will “Tropicalize” as Climate Changes

Release Date: March 18, 2021

Cold-sensitive plants, animals moving north due to fewer, weaker winter freezes

As climate change reduces the frequency and intensity of killing freezes, tropical plants and animals that once could survive in only a few parts of the U.S. mainland are expanding their ranges northward, a new U.S. Geological Survey-led study has found. The change is likely to result in some temperate zone plant and animal communities found today across the southern U.S. being replaced by tropical communities.

These changes will have complex economic, ecological and human health consequences, the study predicts. Some effects are potentially beneficial, such as expanding winter habitat for cold-sensitive manatees and sea turtles; others pose problems, such as the spread of insect-borne human diseases and destructive invasive species.

The researchers found that a number of tropical plant and animal species are enlarging their ranges to the north. They include insects, fish, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, grasses, shrubs and trees. Among them are species native to the U.S. such as mangroves, which are tropical salt-tolerant trees, and snook, a warm water coastal sport fish, and invasive species such as Burmese pythons and buffelgrass.

In the study published this month in Global Change Biology, a team of 16 scientists who have studied the effects of killing freezes describe how many cold-sensitive tropical plants and animals are kept in check by temperate zone winter cold snaps. Warming winters allow these organisms to spread north, especially into the eight subtropical U.S. mainland states: Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California.

Most climate change studies focus on changes in mean temperature rather than changes in the highest highs and lowest lows, so the powerful effects of extreme cold snaps on ecosystems are poorly understood, according to USGS research ecologist Michael Osland, the study’s lead author.

“Extreme cold events are critically important in limiting the spread of tropical species because a short spell of intense cold can kill cold-sensitive plants and animals,” Osland said. “So tropical species can only spread to places where they never encounter killing cold temperatures. But as the climate changes, extreme cold events are expected to become rarer, shorter-lasting, and less intense in parts of the temperate zone. And that opens up new territory for cold-sensitive plants and animals.”

“We don’t expect it to be a continuous process,” Osland said. “There’s going to be northward expansion, then contraction with extreme cold events like the one that just occurred in Texas, and then movement again. But by the end of this century, we are expecting tropicalization to occur.”

The authors document several decades’ worth of changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme cold snaps in San Francisco, Tucson, New Orleans and Tampa – all cities with temperature records stretching back to at least 1948. In each city, they found, mean winter temperatures have risen over time, winter’s coldest temperatures have gotten warmer, and there are fewer days each winter when the mercury falls below freezing.

The authors include scientists from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, University of Arizona, University of California Berkeley, University of California Santa Cruz, University of British Columbia, Louisiana State University and the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust.

Changes already underway or anticipated in the home ranges of 22 plant and animal species from California to Florida include:

- Cold-sensitive mangrove forests have been displacing temperate salt marsh plants along the Gulf and southern Atlantic coasts for 30 years. With sea-level rise, mangroves may also move inland, displacing temperate and freshwater forests.

- Buffelgrass and other annual grasses are moving into Southwestern deserts, fueling wildfire in native plant communities that have not evolved in conjunction with frequent fire.

- Tropical mosquitos that can transmit encephalitis, West Nile virus and other diseases are likely to further expand their ranges, putting millions of people and wildlife species at risk of these diseases.

- The southern pine beetle, a pest that can damage commercially valuable pine forests in the Southeast, is likely to move northward with warming winters.

- Recreational and commercial fisheries are being disrupted by changing migration patterns and the northward movement of coastal fishes.

The authors suggest considering a scientific “rapid response” network to study the effects of cold snaps in the real world as they happen. For example, Osland said “the February 2021 freeze in Texas and Louisiana presented a once-in-several-decades opportunity to better understand the effects of extreme cold events on tropical cold-sensitive species including mangroves, coastal fishes, sea turtles, invasive Cuban tree frogs and invasive Brazilian pepper trees.”

They also suggest in-depth laboratory studies to learn how tropical species can adapt to extreme conditions and modeling to show how lengthening intervals between cold snaps will affect plant and animal communities.

The journal article, “Tropicalization of temperate ecosystems in North America: The northward range expansion of tropical organisms in response to warming winter temperatures” is online at 10.1111/gcb.15563

Authors

Michael J. Osland (U.S. Geological Survey), Philip W. Stevens (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission), Margaret M. Lamont (U.S. Geological Survey), Richard C. Brusca (University of Arizona), Kristen M. Hart (U.S. Geological Survey), J. Hardin Waddle (U.S. Geological Survey), Catherine A. Langtimm (U.S. Geological Survey), Caroline M. Williams (University of California, Berkeley), Barry D. Keim (Louisiana State University), Adam J. Terando (U.S. Geological Survey), Eric A. Reyier (Herndon Solutions Group, LLC), Katie E. Marshall (University of British Columbia), Michael E. Loik (University of California, Santa Cruz), Ross E. Boucek (Bonefish and Tarpon Trust), Amanda B. Lewis (Louisiana State University), Jeffrey A. Seminoff (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

- Categories: