Perspectives from Morgan Chavis, Science Communication Intern with National CASC and NC State

Morgan Chavis, student at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, just finished her Science Communication summer internship supported by the National and Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Centers. This post contains two articles written by Morgan for the NC State Applied Ecology News website. The following is a personal reflection of her summer internship experience and can be viewed here.

My Science Communication Summer at NC State

Hi everyone!

My name is Morgan Chavis and I am a junior biology student at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. When I attended a biology research summer internship seminar, I immediately knew how great of an opportunity this science communication internship would be for me. I have previously completed a neuroscience internship with Delaware State University, however I have never just focused on the environmental side of biology or communications. The thought of researching ecology and climate change seemed fun. I interviewed for this position with Ms. Michelle Jewell and the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center’s team while on spring break in San Juan, Puerto Rico. At the end of my spring break, I received a confirmation email stating that I was SE-CASC’s new science communication intern and that I would be working with the national climate adaptation team at NC State! You can bet that I was jumping for joy in Puerto Rico!

I started my internship by meeting the SE-CASC team and learning about all the amazing things they had planned for me to experience. Before our first meeting, my manager Michelle asked me to make a list of some skills that I’d be interested in learning. I remember wanting to learn more about how to fly a drone, how to edit videos, and to work on my public speaking. One of the very first skills that I was taught was how to fly a drone. Michelle set up a meeting with graduate student Ámbar Torres Molinari and I to learn the specs of a drone and how to fly one. Flying a drone was something that I thought would be difficult but was actually really easy going.

A more thrilling adventure that I experienced was snake hunting! During June, Alex Nelson, her team, and I went to Eno State River Park to search for snakes – specifically snakes with any signs of parasites. We searched under logs and were able to find a few small worm snakes that were completely hidden from the sun and in a dark cool area. We had a hard time actually locating snakes due to the heat – climate being an important part of Alex’s research! The team swabbed snakes to find any signs of fungus while Alex looked for any signs of parasites where we caught the snakes. Alex decided to start identifying the snake parasites to see how and if they were being spread, and how climate change may be affecting that spread. I was very nervous about what I would end up finding or seeing at the park, not being a fan of snakes, so it is safe to say that I kept my distance!

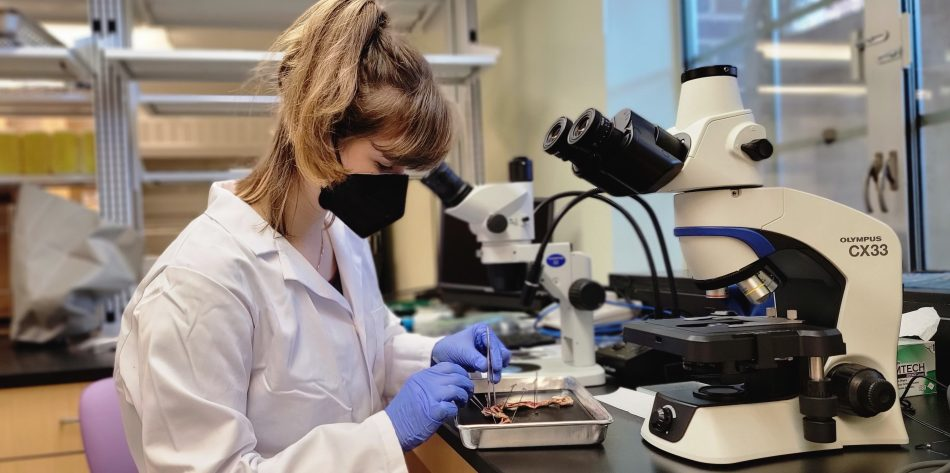

Another nerve wracking, exciting, and cringe-worthy experience that I had was a snake dissection with Alex. We dissected a snake from Richmond County that was donated to NC State by the North Carolina Museum of Science. The snake was a 15.5in long male adult that was preserved by being frozen since 2004! Alex found lots of parasites in the snake and placed them flat on a glass slide to view them in the microscope and identify the parasite types. Identifying parasites in snakes is important since several have never been described before. Check out my article about Alex’s research in A Snakey Situation.

One of my last science communication adventures was deer tracking with Mikiah Carver. We headed to Eno State River Park to locate and track deer. The deer and fawns had collar tags that Mikiah and her team placed on them earlier in the year. Mikiah informed me that she decided to track deer and fawns to understand how long the fawns/deer live, how long they carry their babies, and how long they live in urban environments.

In conclusion, I absolutely had an amazing time with this wonderful team! I am very blessed, thankful, and grateful that this team chose me to be a part of their team. I’ve learned so many new things in such a short amount of time. Something that I truly value within this team is our ability to create a relaxed, open, and transparent environment. Ever since our first time meeting, the team immediately made me feel comfortable enough to confide in them. From meeting up to grab coffees and smoothies, to one on one venting sessions with Ambar who keep me from crying about my summer chemistry course horror story, to absolutely cracking up from my manager Michelle’s hidden humor. Needless to say, I am able to end this summer with plenty of new experiences in science communication, great peers by my side, and lots of new memories!

Morgan’s internship was supported by the National and Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Centers, and facilitated by the Science Communicators of North Carolina.

____________________________________________________________________________

The following article written by Morgan Chavis for the NC State Applied Ecology News website describes one specific activity she participated in as part of her summer science communications internship. View the post here.

A Snakey Situation

It’s not an over-exaggeration to say that we know almost nothing about snake parasites and how common they are in ecosystems. This is a problem because the less we know about parasites, the less we know about their effect on food webs and their potential to spread disease.

If you had told me two months ago that I would have willingly gone into a forest to look for snakes, I would have laughed in your face. And yet, for the past two months, I have been in the field with Alex Nelson and her team to do just that while working on foundational descriptions of parasites in snake populations in North Carolina.

While on a path to conducting her own research and discovery, Alex Nelson – a Ph.D. student and Global Change Fellow, dove into a new world of parasites. Along Alex’s side is Emily Oven – a biology M.Sc. student – who recently teamed up with Alex to cover more ground. They both gather information on new funguses and parasites, where they are in North Carolina, and how they can impact a snake’s environment.

Emily’s main focus is finding snakes and swab them to check for any signs of a new fungal pathogen called Ophidiomyces. This fungus can cause them to develop a mild illness. Alex’s main focus is identifying internal parasites and to try and prevent any potential bad snake health in the future or use these internal parasites to see how parasites can affect an entire ecosystem. Alex also wants to see if parasites can serve as passive indicators of snake presence. If other animals have the same parasites, that may inform Alex that snakes were present within the area – like a natural tracking device.

“Snakes are extremely hard to find in their natural environment,” says Alex. “So, it’s important that we create alternative tools to help us monitor their health.”

In June, Alex, Emily, and I traveled to Eno State River Park with their team. After searching under logs, the team uncovered a few small worm snakes that were completely hidden from the sun and in a dark cool area. Emily swabbed for any signs of fungus, while Alex looked for signs of parasites under the log where the snakes were found.

It was an unusually hot day, so we had a hard time finding the snakes and climate change could be a factor. As humans, we definitely understand the importance of staying cool, however for wild animals staying cool is not a luxury. Being that snakes are cold-blooded, not being able to control their internal temperature forces them to seek out cooler, more hidden areas. This was a minor setback that rerouted Alex to approach her research in a different way and to look for snakes during cooler times of the day.

Alex frequently works in a lab to dissect snakes and see what parasites are inside them. So I joined Nelson for a dissection of a snake from Richmond County. The snake was a frozen, 15.5in long adult male. Inside, Alex found a roundworm, a mite, some eggs, and a cyst. She removed all parasites from the snake, placing them flat on a glass slide and viewed them from up under the microscope to take a deeper look.

Alex will continue to test hypotheses and answer new questions that could be beneficial to her research, like are parasites drawn to certain snakes or are all snakes able to contract this parasite?

Through this experience, I discovered how a snake can be an entire ecosystem. So, the next time I encounter a snake, I will keep in mind how many parasites are actually inside. I will think about how important snakes are to ecosystems and how much they can tell us about climate change in our world.

- Categories: