Tribal Partners

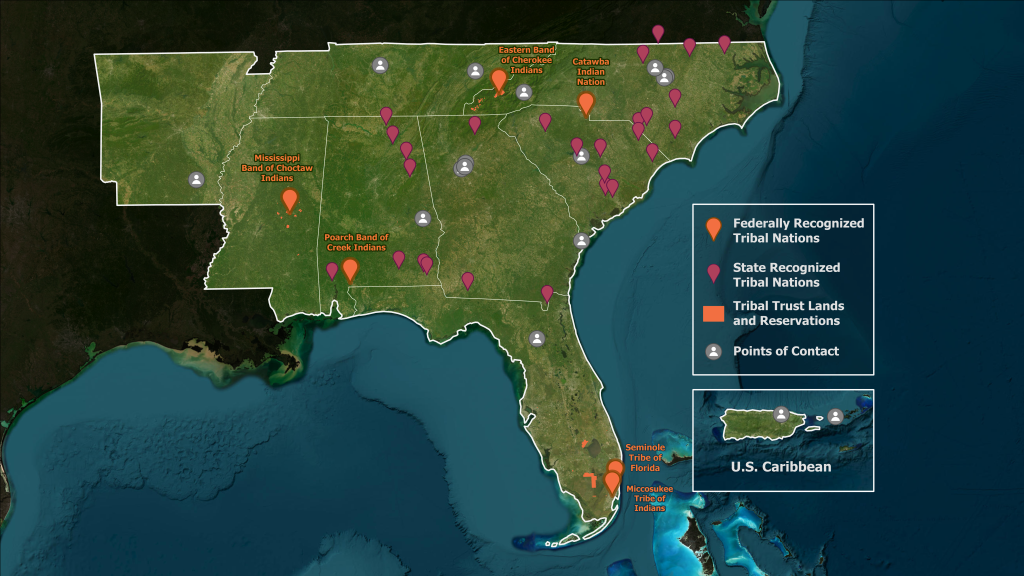

The Southeast is home to several federally recognized Tribal Nations as well as many state-recognized Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities.

There are six federally recognized Tribal Nations whose homelands and waters are within the region of the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Centers (SE CASC). There are also many Indigenous communities that are state-recognized, unrecognized, and/or are currently petitioning for federal recognition. Like other regions of North America, Tribal cultures in the Southeast are very diverse in terms of languages, customs, traditions, and identities.

Tribal Nations are the rightful stewards of homelands and waters; Tribal creation stories, traditions, cultures, languages, and understanding of the world, humanity, and all life forms are intricately tied to these spaces. Tribal Nations possess inherent sovereignty, which means they have autonomous, independent government authority. This sovereign authority includes jurisdiction and governance of Tribal citizens and lands, administration of justice, and, ultimately, the right to make decisions that are best for Tribal Nations now and in the future, including decisions about climate change adaptation and research.

As federally funded institutions, the CASCs are a part of the federal trust and treaty obligation to Tribal Nations. This includes working with Tribal Nations and Tribal agencies (e.g. Tribal environmental, natural, and cultural resource departments and staff) to:

- Identify significant natural and cultural resources that are greatly impacted by climate change and to understand those impacts;

- Identify Tribal information needs to prepare for and address climate change adaptation and concerns, including completing vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans;

- Increase representation of Tribal Nations on SE CASC Advisory Committees, as rights-holders, to achieve parity with representation from states and federal agencies;

- Identify opportunities for Tribal Nations and Tribal agencies to lead and frame climate adaptation research projects that align with their priorities;

- Train SE CASC leadership, principal investigators, staff, and early career scientists in the historical context of Tribal Nations and ethical and best practices in contemporary Tribal engagement;

- Increase the participation of Indigenous researchers and researchers experienced in effectively working with Tribal Nations in SE CASC activities, including among funded researchers and leadership;

- Establish systems for evaluating and monitoring collaborations between Tribal Nations and CASC researchers and/or students to ensure the collaborations continue to benefit all parties involved and address Tribal climate science needs and priorities (i.e., through continued ethical engagement practices).

The CASCs are working to increase and improve their engagement with Indigenous Peoples and increase access to resources for researchers and others interested in applications of Indigenous Knowledges to climate adaptation.

Federally Recognized Tribal Nations in the Southeastern U.S. Map for download

Tribal Climate Adaptation in Context

Unique Histories and Geography of Tribal Nations in the Southeast

Tribal Nations in the Northeast and Southeast are unique in that they were among the first Indigenous Nations in North America to contend with distant European powers in the early 16th century and local colonial governments beginning in the 17th century. From the first contact onward, Tribal Nations engaged in treaty-making with European Nations and then with the United States (U.S.). This was a demonstration of Tribes’ inherent sovereignty and the nation-to-nation relationship between the U.S. government and Tribal Nations that continues to this day. At the same time, Tribal Nations faced colonial wars and disease, which decimated populations. The relationship of Tribal Nations in the Northeast and Southeast with the U.S. government involves a lengthy history of destruction, forced removal, destabilization, termination, and assimilation.

U.S.-Tribal Government agreements often included exchanges of land and resources; these exchanges became the basis for the trust and treaty obligation of the federal government to protect Tribal self-governance, lands, assets, resources, and treaty rights, and to carry out the requirements of federal statutes and court cases.

Lands relevant to the trust and treaty obligation include:

- Trust lands (including reservations) – Lands which the United States has reserved and held in trust for Tribal Nations to assert sovereignty and jurisdiction over affairs. Some federally recognized Tribal Nations have less than one square mile of trust lands, while others still have no trust lands at all. Tribal Nations in the NE/SE CASC are unique relative to other CASC regions in that Tribal trust/reservation lands tend to be smaller than those of Tribal Nations west of the Mississippi River. Many Tribal Nations in the NE/SE CASC are actively working toward the return and restoration of Tribal homelands.

- Ceded Lands – Treaties of Tribal Nations with European Nations and then the U.S. resulted in the cessation of millions of acres of land and natural resources, often involuntarily or out of necessity to prevent further violence on Tribal Nations who sought to protect Tribal homelands and cultures.

- Unceded Lands – Tribal Nations were violently forced from broad swaths of land without any treaties.

These ceded and unceded lands and the natural resources that exist within them are the very foundation of the wealth and power that the U.S. and its citizens enjoy to this day. In exchange, the U.S. made promises that exist in perpetuity to ensure Native people’s health, overall well-being, and prosperity as part of the trust and treaty obligations. Thus, Tribal Nations are not just stakeholders to U.S. government operations, but are also rights-holders.

Tribal Nations who have been removed from their homelands (with or without treaty) also still hold inherent and legal interests in those lands, and must be consulted when the U.S. proposes major changes to those lands. There are over a dozen federally recognized Tribal Nations with homelands in the NE/SE CASC region who are now located in other CASC regions such as the Midwest and South Central CASCs. Tribal Nations are also connected with natural and cultural resources over inland waters, coastal areas, estuaries and oceans. In the Northeast and Southeast, Tribal cultural connections do not stop at terrestrial boundaries, but extend into areas such as the Gulf of Maine, the Chesapeake Bay, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Southeast and Northeast CASCs are federally funded institutions and are therefore bound to honor these trust and treaty obligations. For the CASCs, this duty includes providing the best possible scientific information for Tribal Nations to utilize in climate change adaptation and the protection of Tribal Trust Lands and ceded and unceded Tribal Homelands.

Unique Challenges to Tribal Climate Adaptation in the Southeast

Given the historical and contemporary experiences Tribal Nations in the SE CASC region have faced, climate change impacts and adaptation priorities are unique. Climate change threatens many of the plant and animal species that Tribal Nations rely upon as natural and cultural resources, and many of these species are only found in a particular geographic area or region. Although Tribal Nations across the U.S. footprint have regained the management of natural resources for over 100 million acres of Tribal homelands (~2.6% of the U.S. land base), United South and Eastern Tribes (USET) member Tribal Nations have substantially smaller Tribal land bases from which to assert direct governance, sovereignty, jurisdiction and management of natural resources. Climate change may cause reductions or shifts in certain species’ habitats and reductions in abundance, possibly causing the disappearance of some culturally important species from trust lands. This is an added challenge for Tribal Nations because Tribal trust lands are politically fixed and cannot move with the climate or natural resources. Additionally, the Northeast and the Southeast are home to several Tribal Nations with coastal homelands threatened by sea level rise and storm surge.

Climate change poses serious threats to Tribal cultures and lifeways including impacts on fish and wildlife, traditional foods, medicinal plants, and places of cultural significance, some of which may be outside of Tribal reservation or trust lands. In many instances, places of cultural significance are now located within national parks, monuments, wildlife refuges, seashores, marine monuments, state parks and forests, or on private lands. This means Tribal Nations must also work with federal, state, and local jurisdictions to address climate change impacts on natural resources of cultural and economic significance beyond Tribal lands.

Tribal Nations continue to struggle with non-Tribal jurisdictions for access to locations of cultural significance to partake in cultural activities they have been engaging in since time immemorial. Loss of access to these places, over the last few centuries and in recent times, has greatly impacted the physical and mental health of Indigenous peoples. Climate change threatens sites, practices, and relationships that hold cultural, spiritual, and ceremonial importance and which are foundational to Indigenous peoples.

Tribal-led Climate Change Adaptation and Institutional Barriers

Across the U.S., there are at least 65 Tribal climate change adaptation plans and vulnerability assessments. Some of the first Tribal-led climate change adaptation plans within the U.S. came from Tribal Nations in the NE/SE CASC regions.

The impacts of the 2012 northeastern summer drought/heat wave and coastal flooding from Hurricane Sandy prompted the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and the Shinnecock Indian Nation, respectively, to complete climate change adaptation plans for their homelands, waterways, and communities in 2013. Other Tribal Nations in the NE/SE CASC region are also developing climate change vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans. Certain departments within Tribal governments may take the lead on climate adaptation planning including natural resources or cultural preservation departments, and sometimes Tribal emergency management or economic development programs.

Despite these efforts, there remain significant institutional barriers to Tribal climate change adaptation planning. These include, but are not limited to:

- Limited jurisdiction and access to traditional territory or places of cultural significance;

- Limited staff capacity for climate adaptation work while responding to other threats to Tribal environmental health, lands and sovereignty;

- Funding for long-term climate change adaptation, although there have been recent advances, including the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Often Tribal Climate Change resilience funding remains “project-based” and unsustainable for long-term climate change adaptation plan implementation.

Furthermore, despite federal trust and treaty obligations, Tribal Nations continue to be limited to competitive funding for climate change resiliency projects. Funding therefore remains inaccessible to Tribal Nations with limited staffing capacity, regardless of significant climate change impacts and concerns. In addition, federal natural and cultural resource funding can be very sector-, species-, or place-specific, whereas Tribal Nations are concerned about the health of whole communities and environments. Many Tribal Nations are forced into the position of pursuing multiple grants and searching for funding from different sources with varying objectives in order to address larger climate change impacts on their homelands and communities. Federal funding for climate change adaptation is also at the whim of political power shifts in Congress and the White House. Opportunities available this year may not be available next year, making consistent or long-term climate change adaptation plans, which are critical to Tribal climate resilience, difficult to enact.

One example of a Tribal climate change adaptation strategy is re-acquiring Tribal homelands and placing these lands into trust. Specifically, lands may be selected to provide Tribal communities safety from sea level rise and to provide them with access to species of cultural importance whose ranges have shifted due to climate change. Tribal Nations also seek to restore their homelands and jurisdiction to protect natural and cultural resources. In addition to extremely burdensome and lengthy federal processes to restore their homelands, the 2009 Carcieri v. Salazar Supreme Court decision further challenges the ability of Tribal Nations to have lands taken into trust, even when those lands are within Tribal homelands and territories. Thus, if a location becomes uninhabitable or ecosystems of cultural significance shift due to climate change, Tribal Nations may face additional challenges and opposition.

Ethical Engagement Principles

As with any political, social, or working relationship, there are practices and principles that will make partnerships with citizens and/or employees of Tribal Nations more effective and equitable. We encourage individuals interested in partnering with Indigenous Peoples to learn more using the resources below:

Sovereignty

Tribal Nations, including those not recognized by the U.S. government, possess Inherent Sovereignty:

- “…which means we have autonomous, independent government authority apart from any recognition of such authority by other entities.” (pg. 59, USET Educational Book).

- Indigenous Data Sovereignty is critically important, especially in science and research contexts.

- The CARE principles provide guidance for supporting and reinforcing Indigenous data sovereignty.

- Just like the US federal government and state governments, Tribal governments have agencies with specific duties and authorities (e.g., natural resources departments).

The Rs

There are many important characteristics to ethical engagement:

- The 4 Rs (Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility) describe the need for higher education institutions to better serve the needs of Indigenous students.

- The 7 Rs framework adds Rights, Reconciliation, and Relationships to understand equitable engagement with Tribal Nations and other Indigenous communities.

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)

FPIC is a helpful framework for cooperation with any partners, including Tribal Nations. It describes the only conditions under which consent is truly consensual.

- Free: no coercion or manipulation, such that Tribal Nations don’t need to explain or justify their “no”;

- Prior: before any activities or decisions take place (including project proposals and funding requests);

- Informed: the entire project is clearly communicated in a format, language, and time frame appropriate to Tribal needs.

This includes complete transparency and honesty about the project’s context, activities, timelines, expectations, priorities, potential benefits, public promotion or visibility, weaknesses or potential costs, and more.

A thorough, thoughtful consent process is a requirement of Tribal sovereignty as well. For example, participants must know what information is being recorded, what’s on the record, and therefore what could be subject to a FOIA request. These are potential vulnerabilities for Indigenous data sovereignty, as well as protection of important Indigenous knowledges, sites, and ways of life.

Tribal Community Resilience Liaisons

The Tribal Community Resilience Liaisons for the Southeast are Steph Courtney and Breanna Knudsen.

Direct input from and engagement with Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities is crucial for the NCASC and CASCs to provide the appropriate science needed by these partners. Input is also important so that, when appropriate and acceptable, researchers can understand and consider Traditional Knowledges. Input is, in part, gathered through participation from these communities in the regional CASC Advisory Committees.

Tribal Community Resilience Liaisons at the CASCs help identify research priorities of Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities and work with federal partners to address these priorities. The Tribal Community Resilience Liaisons serve as a technical experts on climate change issues, resource vulnerability, and climate adaptation actions to Tribal Nations across the Climate Adaptation Science Center regions.