Building Adaptive Capacity in a Coastal Region Experiencing Global Change

Southeast CASC project, Climate Change Adaptation for Coastal National Wildlife Refuges, was recently completed. The project team included Mitch Eaton, Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center; Jennifer Costanza, Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, NCSU; Fred Johnson, Wetland and Aquatic Research Center, USGS; Julien Martin, Wetland and Aquatic Research Center, USGS; and Laura Taylor, Center for Environmental and Resource Economic Policy and Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, NCSU and involved extensive engagement with a variety of conservation partners.

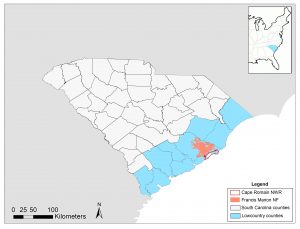

A case study in the coastal plain region of South Carolina

Coastal ecosystems serve as protective buffers from storms, provide food and recreational opportunities for humans, and provide critical habitat for fish and wildlife. Many of these coastal areas are also a source of rich historical and cultural heritage. However, coastal development, climate change, and sea level rise are contributing to the degradation of important ecological and social systems’ ability to remain resilient in the face of disturbance. A coastal community can help maintain or increase resiliency in the event of a disaster by increasing the region’s adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity is the ability to prepare for environmental stressors in advance, or to adjust and respond to the effects of those stressors. The more adaptive capacity a system has, the more resilient it is to disturbances, for example, sea-level rise, tropical storms, and economic downturns.

South Carolina’s Lowcountry

The coastal plain of South Carolina, known as the Lowcountry, served as the backdrop for a case study to identify potential ways in which local conservation groups could work together to devise strategies for adaption planning, and how that might be broadened to include stakeholders with diverse views. Informal meetings, workshops, scenario planning, and other collaborative tools were used to help provide considerations for engaging individuals and organizations interested in adapting to the uncertain future of the Lowcountry. The Lowcountry’s dynamic history has resulted in a resilient, adaptable community; however, this region is now facing rapid environmental and societal change. Expanding tourism and population growth have placed strains on infrastructure, fueled urban sprawl, increased social vulnerability, amplified economic inequalities, and fanned racial tensions in this region. Climate change and other environmental stressors pose an additional set of challenges while intensifying these socio-economic tensions.

A Conservation Community

The Lowcountry conservation community is diverse and focuses on the region’s culture, as well as its ecology. The Cape Romain Partnership for Coastal Protection (referred to as the Partnership) consists of local conservation groups, including: Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, Francis Marion National Forest, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, South Carolina Aquarium, The Nature Conservancy, NOAA Office for Coastal Management, Center for Heirs Property, Lowcountry Land Trust, and South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium.

Tools for Building Adaptive Capacity

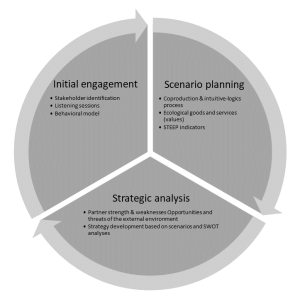

Two informal workshops held in January 2017 and November 2018 brought together members of the Partnership to help explore how the Lowcountry conservation community perceives and pursues its various missions, and how the community might confront the threats and opportunities in its future. By engaging both experts and stakeholders of these social and ecological systems, multiple perspectives and values were considered to help guide adaption planning.

Stakeholder Engagement

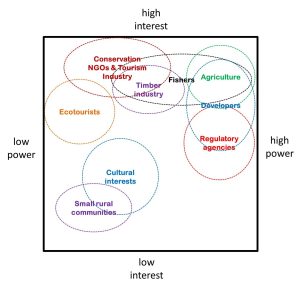

Many entities in the Lowcountry have an interest or stake in the issues of climate change, sea level rise, and land-use change. Each of these stakeholders bring different perspectives and they each maintain different levels of actual and perceived agency to act on issues of concern.

A transtheoretical model (TTM), which suggests individuals move through five phases when changing their behavior, was used to engage stakeholders in the initial workshop. This model encourages a better understanding of the diverse ways individuals and organizations perceive the social-ecological systems in which they are a part of, which helps facilitate more effective engagement and communication strategies. A TTM can also be used to help understand the extent of interest and willingness to act among a broad array of stakeholders from local to national scales. Groups that work in areas further removed from the Lowcountry, for example, national conservation groups or government agencies, are engaged in different ways than those groups operating primarily in the local landscape, like small businesses and homeowners. Applying the TTM helped determine the extent of stakeholders’ interest in, and knowledge of, the changes in the region. Figure 1 portrays nine general groups of stakeholders as identified by workshop participants. Many stakeholders have a high interest in the changes affecting the region, but their perceived power to influence adaptation to these changes varies. Ultimately, this helps to identify areas where more proactive engagement of partners is needed to broaden the Partnership’s message and influence.

Scenario Planning

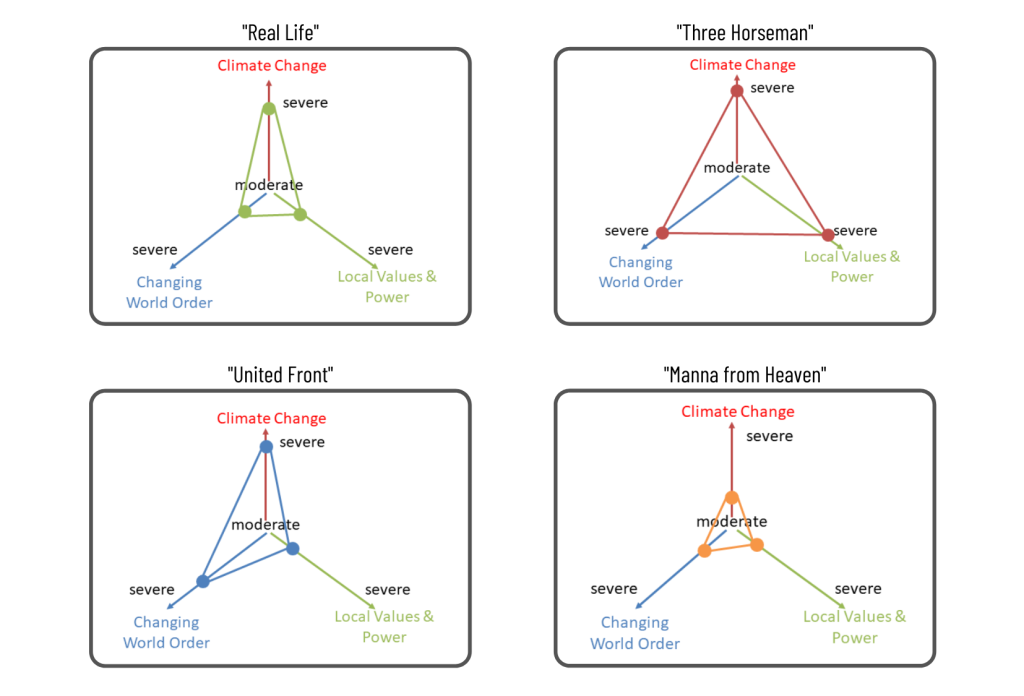

A scenario is a believable description of a possible future state of the world but is not a prediction of what is to come. Planning for these possibilities allows organizations to prepare for an uncertain future. The scenario planning process promotes social learning by fostering greater awareness of social-ecological change and its impacts. In the planning workshops, scenarios were used to help develop strategic actions to help mitigate the effects of global change and emphasized how political and economic trends throughout the world can impact local adaption planning.

Participants individually identified ecological goods and services of value to help focus the development of alternative scenarios. Of those identified, cultural values and provisioning services were of greatest concern. Three principal drivers of change were identified:

– Climate change: Severity of climate change and associated impacts (sea level rise, frequency of extreme weather, etc.)

– Changing world order: National and global social-political shifts have local implications

– Local values and power structures: Social resilience and how individuals and communities organize resources

Participants then characterized “moderate” and “severe” versions for each of the three identified drivers of change to develop four alternative future scenarios, assuming population growth will continue at pace through 2050 (e.g., “Moderate” climate change would have sea-level rise of less than 1 foot by mid-century, while “Severe” climate change would have approximately 2 feet).

SWOT Analysis

SWOT, or Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats, is a tool used to rapidly identify internal and external factors affecting an organization, as well as gain insight into the complex interaction between these factors. Identifying and ranking each group’s strengths, weaknesses, threats, and opportunities in a given scenario helps a group create effective strategies. After examining the internal and external factors, the Partnership was able to develop potential strategies to help mitigate the effects of global change, including:

– Communicate the benefits of existing protected areas in providing ecological goods and services

– Increase conservation community self-awareness (expand partnerships and connect expertise with when, where, how it is needed)

– Conduct outreach in a way that connects quality of life, culture, and demand for ecosystem goods and services with conservation

Findings and Management Implications

Our efforts to support Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge and the Partnership focused on engaging conservation interests and collective decision-making within the larger Lowcountry social-ecological system. However, our work also has implications for other coastal regions faced with complex environmental issues and uncertain futures. Important findings from this case study, include:

- Social and environmental systems do not operate in isolation. Issues affecting one system cannot be addressed without considering the consequences for the other. Addressing these systems in tandem, while also accounting for the important role that attachment to place plays, can help generate social cohesion and facilitate problem solving.

- Developing solutions for complex environmental issues and uncertain futures can be difficult due to the competing values of stakeholders. It is important to respect the pluralities of experience and meaning that stakeholders bring with them to the decision-making process. For the Partnership, using a model of human behavior (for example, a TTM) was key to building adaptive capacity when engaging stakeholders. The TTM recognizes that not all people begin at the same starting place in behavior modification which allows conservation practitioners to design effective messages and activities that better align with what is most appropriate for a specific area, issue, and audience.

- Sustained collaboration between experts and stakeholders can be a difficult process, as differences arise among them in their perception of timeframes, reward structures, goals, process cycles, and epistemologies. However, it can help develop a shared body knowledge which is thought to be an effective way to produce actionable science. Engaging local conservation groups, as well as those who depend on the ecological goods and services provided by coastal ecosystems, can help enhance the likelihood for collective action.

- Recognition of multiple scales of influence was a dominant theme throughout the scenario planning exercises. Local cultural differences, national politics, and globalization all shaped discussions about the region’s future. Throughout our interactions with the Partnership, it became apparent that the conservation community is integral to the broader governance of the Lowcountry’s social-ecological system in which responses to the forces of global change are mediated through local culture, economics, and politics.

- Adaptive capacity depends on the ability to act collectively, and social capital, trust, and organization greatly influence the capacity to act. We suggest that the presence of strong, horizontal and vertical social networks, coordination and deliberation among diverse stakeholders, mechanisms for experiential feedback, and emphasis on social learning are key elements needed to build adaptive capacity.

More Information

Francis Marion National Forest: Adapting to Climate Change. This story map describes how climate change is transforming the region; how land changes and urbanization are affecting the area; and how land managers can improve the resilience of these lands to changing conditions. It was a collaboration between USGS and USFS, based largely on work done for the Cape Romain Partnership for Coastal Conservation and the Francis Marion National Forest Management Plan.

New SE CASC Publication Provides an Extended Framework to Address Conservation Planning Problems

Hedge Betting Climate Change to Preserve Public Lands

Forest “Boneyards” Reflect Climate Challenges at Coastal Refuge

Modern Portfolio Theory Aids Reserve Design Under Climate and Land Use Change

Research Spotlight: Cape Romain Partnership for Coastal Protection

Scientists Work to Understand Conservation Decision Making in the Face of Sea-Level Rise

- Categories: